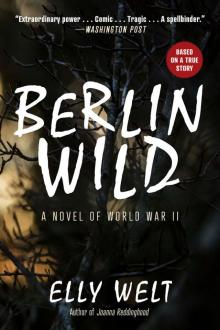

Berlin Wild Read online

Page 7

Mitzka Avilov’s friendship was the greatest of honors, for he was the school leader and hero, adored by students and teachers alike, because he was handsome and clever. That’s how he got his nickname, Mitzka, from amitzka, which in Russian means “pass key” or “false key,” implying someone who could get in and out of any door. He was the one at school, for example, who was able to unlock the door to the bell tower, climb to the top, and wrap his necktie around the clapper so the bell would not ring to announce the end of recess, and all this without even being put on report. He was the ideal Aryan youth—except that he was one hundred percent Russian. He looked just like his mother, Madame Avilov, tall, blond, with purplish-blue eyes, but he had the vitality of his father.

Although he was a year and a half older than I, we were in the same grade. I had been moved ahead a year, and he had remained behind. He was not stupid, to the contrary, but he was not at all interested in schoolwork, only in athletics and girls, and later in politics.

I, on the other hand, had been quite a good student until I was dropped from the rowing team. Mother told me that I was dropped for my own health and that from that moment on I must never again go out on a track field, that I must never again be the class Optimus—even if my grades were at the top—and that I must not stand out or draw attention to myself in any way. I was to become invisible.

So I began to sit in the farthest corner in the back, away from the teacher. I would not speak unless called upon. I took all tests, for not to do so would draw attention to myself, but whenever possible I avoided doing assignments. Sheereen and I became closer than ever.

The school was in the habit of mailing the failure notices to parents immediately before Christmas. That thirteenth year of my life I found only one thing under the tree: an envelope containing a failure notice. I was saved from being suspended by the math teacher who came to our school shortly after Christmas. He was an old man, a retired mathematics professor from the University of Berlin.

He dictated problems, which we were to copy into our notebooks and work out at home, then discuss in class the next day. I always took down the problems but never again looked at them. The second week he was there, he walked about the room picking up notebooks and looking at them. I prayed he would not look at mine. He did. Of course, it was empty but for the questions.

He asked, so the whole class could hear, “Would Bernhardt like to go to the board and copy for the class, from his notebook, the solution and the means to that solution of problem number six of the day’s assignment?”

I looked at my notebook: the questions were concerned with the role of dimensions in physics. Number six was on the derivation of laws governing the oscillation of a pendulum.

I took my notebook to the board and pretended to study it carefully before I began to write. I pretended to copy each step, and in several minutes half of one section of the blackboard was filled. I put a large dot after the solution and underlined it twice, so heavily that the chalk broke.

The Professor said, “Do number seven.”

I repeated my performance.

“Now,” he said, “do number eight, putting only the solution on the board.”

I looked at the question, closed my eyes, pressed my forehead against the blackboard. The figures began to arrange themselves in my mind. When they were through, I opened my eyes and put the solution on the board, crumbling the chalk with the dot and the underlining.

He gave me more chalk and asked me to do numbers nine and ten in the same way. I did.

Then he said, “Now we will do a simple one.” He asked that the class compute in their workbooks and that I do so on the board. “Add together all the whole numbers from one to twenty as quickly as you can.”

Most of the other students bent over their copybooks and began to write down the numbers in a column. I closed my eyes. The numbers danced brightly through my mind; 1 to 20. They arranged themselves in convenient pairs: 1 and 20, 2 and 19, 3 and 18, 4 and 17, and so on. Within five seconds I wrote on the board: 210.

“Josef will now tell us how he arrived at the figure of two hundred and ten.”

I wrote on the board: 21 x 10 = 210.

The old professor came to the front of the room, shook my hand, and said to the class, “You have before you a mathematician.”

I was not suspended from school, and my father bought me a complicated electric train. I refused to play with it.

The math professor began to work with me four times a week until, two years later, when I was fourteen, he told me that he had taken me as far as he could. “All that we can hope for is an early end to the war so that you will be able to study as you should. You have a future in mathematics.”

The day he said that, I thought about it on the ride home on the S-Bahn. It was all that I wanted in the world. If I could study mathematics, I would ask for nothing else. It was during my brief religious phase, and I actually made it into a prayer. But by the time the train pulled into the station at Gartenfield, “hope” and “future” were blue-bleak embers, and in order not to call Providence down upon my head for such selfishness in those times of horror, I made a deal with God and exchanged my life as a mathematician for the life of my mother. I felt noble about this, never dreaming I might end up with neither.

Professor Kreutzer had finished looking through the journals on his desk; he changed from the rimless to the black-rims and handed me ten or so journals he had selected.

“Look at these.”

“When?”

“Why not now?”

The first one went into the application of some dosimetry, had very little text, and was mostly math. To me it seemed but ten seconds later that he asked me what the article was about. I told him that I hadn’t read the introduction yet.

“Read!”

It seemed but ten seconds more when he asked, “What is the important factor in the discharge of the condenser?”

“The replacement of the fixed value in the exponent of e by a differential equation.”

He told me to come back the next day to get more articles and books. There was no dismissal, no good-bye. He turned to a small scrap heap on the table beside his desk and began to change his glasses.

I went back to Krupinsky’s lab carrying the journals.

My good Lord, while I was gone, my work space had been filled with bottles of flies. Sonja Press came in with even more.

“These are most of the common mutations we have in stock. The Chief wants you to be familiar with them by tomorrow.”

She left and I sat at my worktable and stared at the thousands of little fruit flies in the cotton-stoppered flasks. I picked up a flask and looked. All the same to me. I took out the stopper. Three flies clinging upside down to the cotton flew free. In trying to catch them, I squashed one and lost the others. Meanwhile, four or five more escaped from the bottle. I put the cotton back and captured one escapee, put him on my open palm, slowly, slowly moving him closer to my eye. He flew away.

Sonja Press returned with books and journals on Drosophila, realized my dilemma, and explained, “You must anesthetize the little fellows before you can examine them, Josef.” She took the time to demonstrate. “First you put a few drops of this ether, here, on the cotton. Like so. Not too much.”

“Now you tap the flask to shake the flies on the cotton stopper back down, like so. Then you remove the stopper and—very fast—turn the flask upside down, putting the opening into this smaller bottle. You see?” She looked at me.

I nodded.

“Now you tap gently to dislodge the flies but not hard enough to loosen the polenta pudding in the bottom.” She handed the two joined flasks to me. “Here, you try it.”

I did it correctly.

“That’s it. Now stopper the bottle with that etherized cotton. Right! See? You can do it easily.”

When the fruit flies were safely asleep, Sonja had me turn them out on a creased white card, spread them with a tweezer, and then insert the card under t

he microscope.

“Now you can take a look.” She touched my arm. “Before long you will do it with ease. Now,” she explained, “we begin the actual sorting. The useful flies—the virgins and some of the males—we put to one side, like so.”

“What do you do with the unuseful ones?”

“Here. Dump them here.” She pointed to a mass grave—an alcohol jar—heaped with dead Drosophila.

Sonja sat close to me, actually touching, while I practiced transferring the flies from one bottle to another. Before she left, she pressed my arm gently. “Don’t worry, Josef, you are doing just fine.”

She was more than just pretty, and she smelled like roses.

I looked again at the flies. I knew in theory the anatomy of an insect, but to see if there is one vein in the wing missing or if the eye color is yellow instead of red—I just didn’t know. I opened the books Sonja Press had brought in, found the charts with the makeup of each chromosome, and began to read. Her face and body were in my mind, and my arm, where she pressed it, was warm. She was an attractive woman, and I was quite in love with her. Her manner, her warmth, and sweetness, reminded me of Sheereen, although Sonja was nowhere near as beautiful.

I was alone in the lab for what seemed a long time, and I was desperately hungry. The others must have been at lunch. I looked at my wristwatch: almost one o’clock. My time with Professor Kreutzer had not been fifteen minutes or so, but more like two hours. It is always that way when I do mathematics. But it seemed more than the eight hours since I’d eaten breakfast at five that morning.

When they finally returned from eating, they were all different toward me. Krupinsky showed me around the laboratory and explained the work they were doing. The girl whose assistant I was told me her name was Marlene. She was unattractive and had suspicious-looking sore pimples on her face. The Rare Earths Chemist, who was in our lab using some of the measuring equipment, said, “If Krup doesn’t have any work for you here, come into Rare Earths any time.” And they all teased me: “We hear you don’t drink, Josef. Is it for religious reasons?” or “We hear you know something about math, so maybe you can help us with a problem. How much is five times six?”

A marked change. Just like that. No longer “you” but “Josef.” Apparently I had been discussed over lunch. I was relieved. Krupinsky showed me where the bathroom was on our floor, and when I was done at the urinal he explained to me about the shower.

“There’s plenty of hot water here, and you can shower whenever you like.” Then he threw open a huge cupboard filled with clean, starched, white lab coats. “We don’t have any towels, so just use a lab coat to dry yourself. Here. Take off your suit jacket and put this on. Take a clean one whenever you need it.”

I hung my jacket on a hook on the wall, and when I was properly attired, Krupinsky took me down to the first floor, to the cafeteria that served the entire Institute.

“Is this where I eat?”

“Sure, if you’ve got money and ration stamps.”

“I don’t.”

“You mean you don’t have either?”

I hesitated. “Not exactly.”

“Look. Bernhardt, either you do or you don’t.”

“There are other possibilities.” I was quite sarcastic. “I do have both, but they are for my uncle and aunt. I’m going there after work today.”

“What about the pile of garlic you’ve been carrying around? Didn’t you bring a lunch?”

“No. That’s for them, too.”

Krupinsky led me back to the second floor and took me into a small greenhouse off the Genetics wing which had a tiny kitchen where, I soon realized, there was always a pot of polenta for the personnel. He turned on the gas, and while the polenta was warming, lectured to me. “We use this stuff to feed the yeast which feeds the fruit flies,” he said. “For us we cook only cornmeal, water, and a little salt. For the yeast we added molasses, agar-agar, which is a dried algae to make it stiffer, and nipagin, which is a benzoic acid derivative—a good preservative that prevents mold but allows the yeast to grow.”

He ladled a bowlful of the warm yellow porridge, then drowned it in thick brown molasses. My impulse was to rip it from his hands and drink it in a gulp, but I restrained myself and waited while he dug around in a drawer for a spoon. Then, slowly, I spooned in the first mouthful. My hand shook so, I was embarrassed. Hunger is dehumanizing and humiliating. I did not like to eat in front of others when I was so famished.

“Would you like a glass of vodka?” Krupinsky nodded toward a huge vat filled with clear liquid, which I had assumed to be water. There must have been seven or eight gallons of vodka in that vat.

“No, thank you.”

“We can eat and drink as much as we want here, but it is against the rules to take any home with us.” He very kindly left me alone for ten minutes or so while I wolfed down four more bowlfuls. It had been eight hours since I’d eaten my meager breakfast, and I had gone to bed hungry the night before. Perhaps that was why it wasn’t sitting too well. I felt queasy.

Krupinsky breezed in waving several pages of newspaper. “You’re taking money and ration stamps to an uncle, you say?”

“And some food. Uncle and Aunt.”

“What is their name?”

“Jacoby.”

“The Chief said you can take them some cornmeal.” He rolled the newspaper into a cone and filled it with the dried meal, then filled a small flask with molasses. “Be sure to bring the flask back,” he said as he corked it. Then he looked quizzically at me. “You O.K.?”

I nodded yes.

“You look kind of pukey,”

The polenta was sitting uneasily in my chest; I was going to regurgitate the whole mess. “I’m just fine, thank you,” I said weakly. Beads of perspiration on my forehead, weak-kneed, I felt faint. “I think I’m going to vomit.”

“You’re white as chalk. Here, sit down in this chair and put your head between your knees.”

I dropped into the little wooden chair in a corner and put my head down. I could hear Krupinsky fiddling around in the refrigerator. “Give me your wrists,” he said.

I extended both arms and he rubbed ice cubes on my wrists and then on my temples, and the nausea abated somewhat. He put the ice cubes in my hand. “Keep rubbing.”

“Shall I keep my head down?”

“Doesn’t hurt. How’re you feeling?”

“Better. Thank you.” I tried to take a deep breath but had trouble expelling it, which made me sweat even more. “I’m having trouble breathing.”

“Just relax. You’ll be O.K.” He grabbed a tumbler from the cupboard, tilted the vat of vodka, and poured me a stiff drink. “Drink this.”

It must have been three or four ounces. I hesitated, but he shoved it at me. “Drink!”

I took a sip.

“Chug-a-lug. All of it.”

I drank about half in the first gulp and the rest in two or three shorter sips.

“Now take a deep breath and push the air out of your lungs. Push in your gut.”

I did, and the exhale was a powerful belch emanating way deep down inside. “Whew. That’s better,” I said, pounding lightly on my chest. I could breathe, wheezily.

“You have asthma?”

“I used to when I was younger. Thank you, I think I’m quite drunk.”

“You’ll be O.K. What we usually do around here is space the polenta out through the day—a bowl or two when we get here, and now and then during the day; then, before we leave, we often come in and have one more and a snort of schnapps to get us through the trip home.”

He gathered up the cornmeal and molasses for my uncle and aunt, and we returned to the Biology Lab, where I fell into the chair at my worktable and put my reeling head into my hands.

I was drunk for the second time in my life. The first time, my father had settled a huge case and his client invited him to a restaurant in the village for dinner. For some reason, he took me along—I was six years old—and they ordered a bo

ttle of champagne. No one paid any attention to me, and I gulped down several glasses of the pleasant-tasting stuff before they realized it. I felt quite contented, but my lips were numb, and the singing seemed to come from a great distance. I turned to locate it, a reedy tenor voice singing a corny Italian art song, “Caro mio ben,” and as though through the wrong end of the ocular on my microscope, smaller and far away, at the lab entrance, stood Professor Avilov—the Chief—in a white lab coat and, behind him side by side, two clowns, a tall, thin one, also in a lab coat, and a short, fat one, a dumpling with a bay window, in a dark suit with vest. He was the one singing, the dumpling, and he had a vibrato so terrible that he never seemed to hit a note directly.

The Chief’s arms were outstretched, and he held a glass bowl, like an offering. “Sunflower seeds, anyone?”

Then the tall, thin one in the white lab coat leaped forward like a dancer and said, dramatically, “My dear Krup, how many flasks do you need for the new cultures?” He wore shiny black pumps.

Krupinsky assumed a mock ballet position and said, “My dear Yugoslav, why don’t you tell us about Belgrade?”

The Chief, stepping forward into the lab, repeated, “Sunflower seeds, anyone?” and the dumpling, still singing, swooped over to pimply-faced Marlene. “Credi m’al men,” he vibrated in her ear.

“Belgrade!” The Yugoslav twirled about. “One cannot speak of Yugoslavia without music,” and he catapulted into the center of the room and began to dance in earnest—rather fine dancing. I found out later that in Belgrade, he had been a professional ballet dancer, and that now he was a zoologist doing neurophysiological research with primates and other animals. The singer was a Russian named Bolotnikov. He did genetic research with Ephilachna, a kind of ladybug, and he grew sunflowers in the greenhouse off the first floor to feed his ladybugs; consequently, there were always plenty of seeds to eat.

Berlin Wild

Berlin Wild