Berlin Wild Read online

Praise for Berlin Wild

“Extraordinary power . . . Comic . . .Tragic . . . A spellbinder.”

—Washington Post

“A powerful and absolutely stunning achievement. Welt’s characters etch themselves on the memory. . . . On all scores, including consideration strictly from a literary point of view, Berlin Wild is a glorious, smashing success.”

—Chattanooga Times

“Earns four stars . . . A wonderful book . . . Read it, by all means, and give it to a friend.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Moves you to laughter and to tears. . . . One could rhapsodize about this marvelous book. . . . It is among the important books of the year and decade.”

—Louisville Courier-Journal

“A stirring tale of the nature of survival.”

—Boston Review

“Taut . . . Remarkable . . . Deeply searching . . . Moving . . . Cliffhanger suspense . . . A crescendo of emotions . . . A thriller . . . A triumph!”

—Publishers Weekly

“Vibrant with warmth, humor and vitality of those clinging to the brink through wit and will.”—Kirkus Reviews

“Wonderful . . . Rivaling Catch-22.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

“The mature work of a gifted writer . . . Stunningly macabre . . . A moving, heartbreaking story told with grace, style, and some very black humor.”

—Fort Worth Star-Telegram

“Highly literate, excellently written, and totally absorbing.”

—Library Journal

“Memorable, funny, frightening, sardonic, sad, and utterly authentic. . . . Has the force and veracity of a personal testament.”

—London Magazine

“A stunning portrayal of sanity in the midst of madness, humor in the midst of tragedy, and humanity in the midst of the greatest horror in history.”

—Nine to Five

“This novel hooks the reader on the first page and does not let go.”

—USA Today

“Pain and laughter . . . The author had the genius to allow comedy to dominate this powerful story of struggle.”

—The Washington Book Review

“A brilliant black comedy . . . Daring, original, mesmerizing . . . A prodigious feat carried off with the absolute assurance of a master.”

—Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“A veritable mine of a black and other kinds of humor—ironic, broad, high . . . Appreciation of the absurd . . . Provide its fine cutting edge.”

—Chicago magazine

“Stunning and rewarding . . . The work of a master of dark humor . . . Able to evoke every emotion from the most tragic of situations.”

—Kansas City Star

“Exquisitely crafted . . . Funny . . . Moving . . . Compelling . . . Engrossing . . . Vital.”

—Newsday

“May be the subtlest book ever written about the sufferings of Europe’s Jews at the hands of Nazis. . . . Gives fresh tension and suspense to the terrible story . . . One of the best books of the year . . . One of the best I’ve ever read.”

—Chicago Tribune

“A rich, vibrant novel. . . . A stunning achievement. . . . A highly original and deeply felt tragicomic vision of twentieth-century life.”

—Houston Chronicle

Also by Elly Welt

JOANNA REDDINGHOOD

For Peter my love

Copyright © 1986 by Elly Welt

First published in 1986 by Viking Penguin Inc.

First Skyhorse paperback edition, 2020

Excerpt from “Bells for John Whiteside’s Daughter” from Selected Poems, Third Edition, Revised and Enlarged, by John Crowe Ransom. Copyright 1924 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and renewed 1952 by John Crowe Ransom. Reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf. Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Welt, Elly, 1932–2018. Berlin wild.

1. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Fiction.

2. Berlin (Germany)—History—1918–1945—Fiction. I. Title.

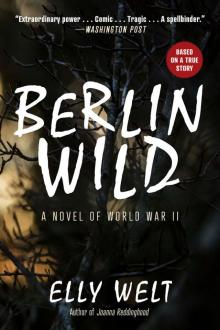

Cover design by Daniel Brount

Cover photo credit Doug Plummer

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-5698-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-5699-1

Printed in the United States of America

I am thy father’s spirit;

Doom’d for a certain term to walk the night.

And for the day confined to fast in fires.

Till the foul crimes done in my days of nature

Are burnt and purged away.

—Hamlet (1, 5)

If I were to tell you the truth I would have to lie.

—The Chief

Contents

PART I. OCTOBER 10, 1967, IOWA CITY

CHAPTER ONE: Winemakers

PART II. 1943–1944 BERLIN

CHAPTER TWO: First Day

CHAPTER THREE: Sheereen

CHAPTER FOUR: The Smells of Eden

PART III. OCTOBER 10, 1967, IOWA CITY

CHAPTER FIVE: Elizabeth

PART IV. 1944–1945 BERLIN

CHAPTER SIX: Liberation of Paris

CHAPTER SEVEN: Berlin

CHAPTER EIGHT: Last Day

PART V. OCTOBER 10, 1967, IOWA CITY

CHAPTER NINE: Kaddish

PART I

October 10, 1967,

Iowa City

CHAPTER ONE

Winemakers

ON TUESDAY, OCTOBER 10, 1967, the day the surgical resident advertised him as the German who just came down from McGill, Dr Josef Bernhardt realized he had been in a depression since the end of the war. Not a clinical depression—he was functional—but in an emptiness lasting twenty-two years.

“Who is he?” the circulating nurse had whispered to the surgical resident.

“He’s the German who just came down from McGill.”

His patient was asleep and already paralyzed, and Dr Bernhardt was preparing to insert the endotracheal tube before turning him over for surgery, when he noticed that the resident was folding down the sheet.

“He’s not intubated yet. Cover him, please.”

But the resident, preoccupied with the pretty circulating nurse, continued to fold down the sheet, exposing the naked body of the patient, an elderly black man. Dr Bernhardt kicked at the tripod stand holding the unwrapped sterile water basin. The empty stainless steel container clattered on the tile floor. All looked at him: the surgical resident and the circulating nurse, the intern, the orderly, the scrub nurse, and the surgeon.

“Cover him!” Dr Bernhardt shouted, voice shaking, body trembling with rage. His large, dark eyes above the white mask were half closed with pain. He could see his pulse, rhythmic, making waves, distorting his vision, and feel his diffuse headache throbbing in tune.

The reflexes of the resident and the circulating nurse were a jump and a rush to pull up the sheet. Hands met. Heads bumped. They covered him.

“This is Mr LaRivière,

” said Dr Bernhardt, extending his arm. “If he were awake and in control, would he wish to expose his genitals to you in such a way?”

The resident and the nurse shook their heads, faces drained of color.

“Then while he sleeps, you will treat him with the same consideration as you would if he were awake. And if I hear again of such indignity to a patient in this hospital, the wrath of the Lord will descend upon you, and it will come through me.” He bowed slightly to the surgeon. “I beg your pardon, doctor.”

“Thank you, doctor, very much,” said the surgeon.

“Who is he?” hissed the nurse.

“He’s the German who just came down from McGill.”

The operating room was small; Dr Bernhardt could not help but hear. He, at the head of the table, hemmed in by the anesthesia machine with its gas cylinders, valves, and meters, could not escape, for LaRivière was asleep and already paralyzed.

The anesthesiologist must interview his patients while they are fully conscious. Josef Bernhardt visited LaRivière on his rounds the afternoon before surgery, having no idea that this would be his final case. At the station on Four North, a nurse handed him his chart.

“Thank you,” he said mechanically, without seeing her. He leaned heavily against the counter and opened his second pack of cigarettes for the day, feeling so tired that any movement was extraordinary effort.

“Dr Bernhardt? May I get you a cup of coffee?”

“I beg your pardon?” He glanced at her face—young, late twenties or so. The name tag on her left breast read Susan Ingram, R.N.

“Coffee? May I get you a cup?”

“No, thank you. Miss Ingram. But if you have an ashtray?”

She turned away and was back in an instant.

“Thank you very much.” He extended the pack of Camels. “Would you like a cigarette?”

She shook her head. “I think you smoke too much.”

Her face was even-featured and pleasant, her dark hair pulled back neatly behind the stiff white cap.

“You are right.” He leafed through the chart, several pages on a clipboard. “Are there any old charts?”

“No. He hasn’t been in a hospital for thirty years, and that was in France and was some kind of fracture.”

Dr Bernhardt lit his cigarette.

“I’ll see if I can get the lab reports up before you leave the floor.”

“If you would be so kind. I would really appreciate that.”

She addressed a student nurse who sat at a desk at the rear of the station. “Telephone the lab, please, and see if you can get the results on Mr LaRivière before Dr Bernhardt leaves the floor.”

“That’s the pilondial cyst in four-oh-nine North,” said the student.

“His name is Auguste LaRivière.”

“He’s the cranky old colored guy in four-oh-nine North.”

“His name,” repeated Miss Ingram, “is Auguste LaRivière.”

Auguste LaRivière, 72, Professor of Chemistry, retired. R.C. No Last Rites. The nurses’ notes listed many complaints: that the nurses would not let him sleep; that they awakened him to give him a sleeping pill he did not want; that they would not tell him the name of the sleeping pill; that they restricted him to his room and would not let him go down to the cafeteria; that they took away his bottle of wine. All in all, the patient seemed crotchety but fit.

Dr Bernhardt extinguished his cigarette and was about to walk down the hallway.

“Wait a minute, Dr Bernhardt.” The student nurse was waving a piece of paper and moving toward him. “I’ve got the lab tests.” She came out from behind the counter to hand it to him. “How do you like it so far in Iowa City?”

“Fine, thank you.” He looked at the paper: routine preoperative lab work was well within normal limits. No obvious problems.

“Do you mind if I ask you a personal question?”

Reluctantly, he looked up. “I can’t promise to answer.”

“Are all the anesthesiologists up at McGill like you and Dr Borbon? He came from up there too, didn’t he?”

“Yes.”

“Do you want to know what the girls are saying about the two of you?” She giggled and leaned provocatively close. “They say you’re good-looking enough to be obstetricians.” She was a blandly pretty blond, typical of the region, corn-fed and bursting with health. “Dr Borbon says that obstetrics is the only specialty chosen while standing in front of a mirror.”

“I’ve known it to happen, Miss . . .”

“Burke. Debby Burke: 555-4765. And I’m partial to older men.”

The station nurse, Susan Ingram, was still at the counter. Dr Bernhardt looked at her; they exchanged smiles. She was a small woman, full-bosomed. Her crisp white uniform was buttoned to the throat, and she wore a thin gold chain under the collar with a small peace symbol resting between her breasts.

“And I like your accent.”

“You’ll have to excuse me, Miss Burke.”

He clipped the lab report onto the chart, walked down the hallway to 409 North and knocked on the door.

“C’est ouvert.” The voice informed, curtly, in French, that the door was open.

Dr Bernhardt entered and scrutinized the patient: LaRivière sat up in bed reading, a red plaid robe over his pajamas. Magazines and newspapers were stacked neatly on his bedside table. His slippers were so placed on the stool beside the bed that one could assume he walked freely about. He was in no obvious distress: if anything, he was at ease and fully in control of himself. He was a Negro, so dark that Dr Bernhardt could not tell whether or not his color was good, but there was no obvious breathing difficulty and no evidence that he smoked. Although his hair was gray, he looked younger than seventy-two.

“Good afternoon, sir. Are you Mr Auguste LaRivière?”

“It is I.” The patient spoke English with a pronounced French accent.

“Excusez-moi, Monsieur LaRivière. Je m’appelle Josef Bernhardt. Je suis votre docteur, votre anesthèsiste.” Their conversations, thereafter were in French. “I will be putting you to sleep before your surgery tomorrow.”

“You’ll be administering anesthesia, you mean. Contrary to your opinion, monsieur le docteur, not all of us with dark skin are in want of education. I have a doctorate from the Sorbonne. But I should not correct you. At least your French is perfect. Nevertheless, you will forgive my hopefully incorrect assumption that you are like the rest of them and won’t tell me what you are going to give me.”

“What kind of anesthetics have you had before, monsieur?”

“Ether! Once!”

“Have you any allergies?”

“They asked that before. It should be written.”

Dr Bernhardt looked at him without speaking.

LaRivière glared fiercely, but the doctor remained silent.

“All right, doctor, there’s not a thing in the State of Iowa I’m allergic to but the racial bigots and being wakened in the middle of the night to be given a sleeping pill they won’t tell me the name of.”

“How much alcohol do you drink?”

“Do you mean here in this prison, or when I’m a man?”

The doctor waited.

“You’re not a talker, are you?”

Dr Bernhardt shook his head.

“Hmpff! Every night at home—with my dinner—I drink a small bit of my own homemade wine. One glass or two. I brought some with me, but the nurses made my wife take it away. Then at night, when I get into bed, I sip a little Scotch whisky with the ten o’clock news before I go to sleep.”

“How do you take your whisky?”

“I used to take it pure, but my stomach can’t stand that now, so I mix it with a little water. Are you going to tell me what you are giving me in the morning?”

“Laughing gas.” Dr Bernhardt smiled.

“Nitrous oxide? That won’t even touch me, much less put me to sleep.”

“It will be combined with other drugs.”

“What other drugs?

Sacrè coeur, doctor, if you would look at my chart as you are supposed to, you would see I’m a chemist!”

“Sodium thiopental to put you to sleep. Succinylcholine to paralyze you and small doses of meperidine, nitrous oxide plus oxygen for sleep and analgesia.”

LaRivière was startled. “Succinylcholine. That’s a muscle relaxant.”

Dr Bernhardt nodded. “It blocks the nerve impulse to the muscle by keeping the neuromuscular junction in a state of depolarization.”

“But why would you want to paralyze me? I won’t be able to breathe!”

“I do so that the level of sleep need not be very deep. One needs less of the drugs. And I am there to breathe for you.”

“Artificial respiration,” he said quietly.

“Yes. In the morning before they take you up to surgery, you will be given shots of meperidine and Nembutal, and also some Bellafoline to reduce secretions. I see from your chart you prefer not to have a sleeping pill at night.”

LaRivière nodded.

“I’ll leave an order for a glass of wine with your dinner and at eight o’clock or so a shot of Scotch whisky and water. After that, please, nothing by mouth until after your surgery.”

“I thank you, doctor.”

“You’re welcome.” LaRivière seemed shaken, chastened. Dr Bernhardt had not intended that. “I would like to apologize in advance for the wine they will bring you. It will not be like your own.”

“You’re damned right it won’t,” LaRivière exploded in English; and then, in French, “It’s those nurses. And my wife—she took mine away. Did you ever make your own wine, doctor?”

“No. But I remember that my uncle did.” For an instant the image surfaced in Dr Bernhardt’s mind of the bulging cheesecloth, stained wine-red, dripping over the bucket in the cellar of his uncle’s apartment house in Berlin. Passover wine. “It was for sacramental purposes. Very, very sweet. As a child I loved it.”

“He must have used sugar. I add no sugar! Only the grape. I add no yeast! My hands and the grape, which I grow myself.”

Berlin Wild

Berlin Wild