Berlin Wild Read online

Page 6

That sounded pretty good to me, and I allowed myself some comfort from Calvinism, the religion of my father, until within two months, during chapel, I suspected what a swindle it was, too, and that there was no one of my parents’ generation who had any sense whatsoever. A visiting minister preaching the sermon that day insisted that one did not question Paul, who said that the governing authorities, without exception, are ordained by God and are God’s servants. To support his argument, he read from Romans 13: Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is not authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God.

Immediately following the service, I sought out our school chaplain, who was standing at the front of the chapel. “Surely, Herr Wäsemann, he cannot mean that Adolf Hitler is God’s servant?”

I could see our chaplain was upset by my question. “It is ambiguous, Josef, and there is much argument among the clergy.”

A fellow student, Dieter Schmidt, who had also approached Herr Wäsemann, overheard our conversation. “My God,” he blurted out, “Saint Paul could never have meant that a government of criminals was ordained by God.” Dieter Schmidt was as much an outsider as I, not because he was a cross-breed but because he was from a working-class family. There were even rumors that he was a Communist, and behind his back the other students called him “Commie.” At the time, I didn’t believe it, for he was quite religious. However, I found out later that I was wrong.

Dieter Schmidt talked so loudly he drew attention to us, and the visiting minister walked over to join the discussion. “Luther himself,” he said in a condescending tone, “wrestled with these verses, and in his famous footnote to Romans 13 he teaches that in contrast to the Jewish idea, one should be obedient even to evil and unbelieving rulers—”

“But wait a minute!” said Dieter Schmidt.

The visiting minister held up a finger to silence Dieter and raised his own voice about ten decibels. “And he quotes from Peter, who says that everyone must be subject to every human institution, whether it be to the Emperor as supreme or to the governors as sent by him, for, as Luther explains, it is God’s will!” The visiting minister was thundering now. “Even though the powers are evil or unbelieving, yet their order and power are good and of God.”

“I don’t believe it!” shrieked Dieter, losing his head completely and drawing a group about us. “Luther was a revolutionary who broke the rules of those religious authorities governing him when he knew they were wrong and when they went against his conscience. We know our present government is wrong and goes against our conscience—and compared to the malignancy of the Nazis, the Catholic Church in Luther’s time was benign.”

Herr Wäsemann, crimson, gasped, “Schmidt! This impertinence will be recorded in the Daily Diary of your class!”

Now we were surrounded by faculty and many students. One of the older students, who wore the brown uniform of the Nazi Youth, with much gold braid about the shoulder, stepped forward and addressed the school chaplain directly. “How do you interpret it. Heir Wäsemann?” It was a dangerous situation.

Voice shaking, Herr Wäsemann answered, “Romans 13, Verse Two, merely reinforces One: Therefore he who resists the authorities resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment. That is”—he paused—“they will receive damnation.”

At this, Dieter Schmidt wheeled about, strode out of the chapel, and disappeared. I did not hear of him again for years.

Another teacher, also a minister, ashen-faced, stood now beside the chaplain in a protective way. “Say what you will,” he said, “we are servants of the State. We have all signed a loyalty oath”—he raised his voice so all could hear—“and I, for one, and Herr Wäsemann here, for another, will not go back on our word.”

“Heil Hitler!” Up shot the right arm of the body in uniform, who then looked at the chaplain for affirmation.

Herr Wäsemann, stony-faced, nodded, as though in agreement, and walked woodenly down the center aisle of the chapel and out the door.

There was no door to the penthouse. One came up the spiral stairs and stepped into the reception room. I heard steps: Max?

Max! Herr Doktor Professor Maximilian Kreutzer, the physicist of the junkyard, appeared. His hair was graying, his face stern, his clothes impeccable. He stood straight, a bit of a belly. He looked very important and authoritative. He wore eyeglasses. He strode past me and knocked twice—two quick, hard raps—on the door of the private office.

“Enter.”

He entered, slamming the door behind him.

They emerged together. Professor Avilov began to pace. Professor Kreutzer, across the room from me, took from his pocket a glasses case, removed a pair of small round spectacles with a narrow black shell rim, and returned the case to his pocket. He extracted from another pocket a small patch of cloth and began to clean the spectacles, looking at them through the gold-rims he was wearing, holding them to the light of the window and then to the light of the electric fixture in the center of the room. When he seemed certain they were clean, he removed those he was wearing, slipped them into the case, returned them to his pocket, and put on the black-rims.

Then he looked at me, a direct stare, but over the black-rims, or so it seemed, and not through them. Then, my good Lord, he pulled another case from his pocket, removed from it a pair of small round rimless spectacles, and, using the same cloth, cleaned them, holding them this way and that, and, when he thought they were clean, removed the black-rims and put on the rimless. He placed the black-rims in the case and put them in his pocket.

He looked at me. Directly, through the glasses, he stared.

I could not meet his eyes. I, little dog, looked at the floor. Professor Avilov still paced, hands locked behind his back, humming a quiet tune. When Professor Kreutzer was through staring at me, without a question to me or a word, he took from his pocket the original gold-rimmed glasses and repeated his cleaning and changing routine once again before he was able to say to Professor Avilov, “Why don’t you call Krupinsky and tell him he has a new lab assistant?” That was all. He strode off. Professor Avilov ran after him, down the spiral staircase, returning shortly with that Krupinsky person from Biology who had rejected and humiliated me already.

Professor Avilov pointed to me. “This boy has to work here.”

Krupinsky said nothing.

“He’s in the same boat as you.”

Krupinsky made some kind of motion with his hands and shoulders, a complicated shrug which one could read as You win or All right, I know when I’ve lost. “O.K., Chief,” he said, “what do you want me to do with him?”

“I’ll tell you, Krup: he doesn’t smoke, he doesn’t drink, and I assume he doesn’t . . . Teach him. He’s all yours.”

“Sure. What school does he come from?”

“Collège Français de Berlin, the same as Mitzka.”

“Come along,” said Krupinsky.

I picked up my jacket and rucksack from behind Sonja Press’s desk and followed him. On the way to his lab he asked me questions.

“Do you listen to the BBC?”

“No,” I lied.

“Do you know English?”

“No.” Actually, I could read it, but I felt no need to tell him.

“Do you want to study medicine?”

“No! Never!”

Although he was in charge of the largest Biology Laboratory in the Genetics and Evolution Department, he was not even a real scientist—just a medical doctor.

There were two other men in the lab and two girls. He said to one of the girls; “He will be your assistant. Show him how to use the microscope, how to handle the flies, and what kind of labeling system we have here.” And he left.

It was ten in the morning.

The girl pointed to one of the binocular microscopes on the worktable in front of the window. “This one is yours. Come along.” Then she led me out of the lab and down two flights to a basement storage room. There,

in two large suitcases, were the extra parts to my microscope. I carried both suitcases up to Krupinsky’s lab. The girl told me to fix it so I could sit and look through “that thing” for hours at a time.

It was a beauty, a Greenough binocular with paired objectives and paired eyepieces, with Porro prisms for erecting the image. It had a large dissecting table attached, and a place to put my arms so I could lean comfortably into it as I worked. As with the microscope of the kind woman biologist, Frau Doktor, this, too, permitted one to look straight ahead, rather than down, to see the objects below. I opened the two suitcases and prepared to see what the possibilities were, but the girl was back with two trays filled with small bottles which she had taken from incubators lining the entire wall behind me. Each bottle contained ten to fifty fruit flies.

“Look at these Drosophila. See how they are labeled. Become thoroughly familiar with them by tomorrow.” She left and came back with two more trays and two more.

My good Lord, they all looked alike to me. What was I looking for? Virgins and cubitus interruptus? Krupinsky returned: he had been gone an hour or so. “You’re supposed to go over to Physics,” he said to me. “Kreutzer wants to see you.”

I left the trays of Drosophila on my worktable and walked down the hall to the Physics Lab, where I found Professor Kreutzer behind the desk in his office. There were journals and books scattered everywhere and a table beside him heaped with scrap metal and other junk.

“Sit down!” He changed from the rimless to the black-rims before he addressed me again. “What do you know about ionizing radiation?”

I did not know what to say. I had read about it in the science periodical Die Naturwissenschaften and had heard several lectures on nuclear physics at the Technical University by a physicist named Heisenberg.

“Well! Speak!”

“I know there is something like it.”

“You will have to know quite a lot more than that by next week.”

I shrugged.

“What is your background in physics, chemistry, biology?”

Again, I shrugged. I did not mean to be rude. It was difficult for me to speak about myself.

“Listen! Professor Avilov knows you, and he is not an idiot. So don’t try to lead me to believe that he does not know what he is doing when he recommends you. He would not send a idiot to waste my time.”

I said, “I have not studied—”

“I am not interested in what you do not know. I am interested in what you know.”

“I have some elementary knowledge in basic sciences but it is all hypothetical, not even theoretical, and there was no practice involved. In the sciences, for the most part, I have read books and passed tests; for example, although I never have had a course in qualitative analysis, I read books and journals and passed the tests.” I paused. “With high marks!”

“Yes! Yes! What else?”

“I have a solid background in mathematics.”

He turned from me, changed to the rimless, and began to look through the scientific journals stacked on his desk.

Mathematics: It was that solid background which kept me in the school. Collège Français de Berlin was difficult academically, and many students were failed the first few years. Only those with the best marks were retained. After I was dropped from the rowing team, I almost flunked out.

I was pacesetter, and we were winning. Nevertheless, in 1939, when I was twelve years old, I was ordered one morning to the office of the Director of the school. I had no idea why he wanted to see me; as far as I knew, I had not committed any infraction serious enough for such a summons. When such a crime did occur, the teacher making a charge would send a note to the Director with the complaint: tardiness; leaving the building during school hours to go to the candy shop around the corner; being on report in the Daily Diary of the class more than two times in one week. Diary offenses were, for instance, laughing or talking or any other disruptive behavior in class, inattention, disrespect to the teacher or to other students, and so on.

The malefactor would be sent first thing in the morning to the office of the Director, where a great part of the punishment would be anticipatory, for he was made to wait in the anteroom for what seemed a long time before the secretary would say, “You may go in now.”

Once in the Director’s office, proper form was to bow, click one’s heels, and say, “Heil Hitler.” Also acceptable was, “Good morning, Herr Direktor.”

Herr Direktor would look quite stern. “Bernhardt, it says here that you have been displaying disruptive behavior. What is it you have been doing?”

“I laughed during Latin grammar.”

“I do not want to hear of it again. It is not suitable behavior for a German citizen. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Herr Direktor.”

But that morning in 1939 was different. I was not made to wait, and the Director himself came into the anteroom and beckoned to me. When I followed him into his office, I saw the rowing coach sitting in a chair in the corner.

As I said, I was the team pacesetter, and we were winning.

The Director seated himself.

I bowed, clicked my heels, and said, “Good morning, Herr Direktor.”

He shuffled papers on his desk while he spoke. “Bernhardt, you will no longer be permitted to be on the rowing team. You are not strong enough.” He could not look me in the eye.

Rowing was important to me when I was twelve, and track and field, and winning. But rowing was the most important, and I spent many hours working out. Twice each week I practiced on the rowing machines at the University of Berlin.

The Director’s office was on the second floor and had large, arched windows. I looked out at the River Spree across the way—just a stream, really—and listened to the rowing coach make a weak attempt on my behalf. “He doesn’t look strong, but he is very wiry.”

“He is not strong enough!”

And that was that. At that time, I felt that it was the end of my life.

Word got around school. My friends, Sheereen and Petter, were sympathetic, and Mitzka Avilov, who had never even condescended to speak to me before, stopped me in the hall and said, “You have more stamina than all the rest.” And he began to be my friend, even coming to my house, now and then, to help Petter and me with the secret cave we were digging in my back yard.

It was just a hole in the ground, really, and I started it because I was fascinated by the possibility of finding ground water. Father said the ground water was quite high in our back yard, but I had doubts about it. There was a steady slope downhill to a channel half a kilometer from our house. The channel was deep and navigable, with boats and ships going through. So I thought that since we were uphill from the channel, and that since our very deep laundry cellar was absolutely dry, there couldn’t possibly be water anywhere near the surface. I was certain my father was wrong!

Petter was with me the day I started digging, and I was so sure there would be no water that we planned to dig a secret cave and play Trappers and Indians. I had the mistaken idea they mostly lived in dugouts. Digging wasn’t at all difficult since Berlin was in a glacial stream valley, and the top soil was moist sand and clay. We were very careful to hide all the earth we dug up, and we obscured the entrance so cleverly that I thought my parents would never discover what we were up to.

But two weeks after we’d begun, I was shoveling away, and there, at my eye level, were Father’s black shoes and gray spats. I expected he would put an end to the whole thing, but he didn’t. It was several weeks after I had been removed from the rowing team, and my parents had been making an effort to divert my mind—to keep me busy with white mice and pigeons, books and radios.

“Josef!” said my father. “Because it is so easily dug and so hard to maintain, you will need to support the walls with lumber.”

I was quite astonished that he even knew anything like that. At that time I still thought Father was an impressive person, but I didn’t think he knew how anything worke

d. Later, Mother told me that he had been an officer in the Pioneers—the corps of engineers—during the First World War. “If it had not been for me,” she said, “he would now be a high officer in the army.”

“I have no lumber, Father.”

“Yes. I have opened a charge account for you at the hardware store. You may buy what you need.”

I had another open charge at the bookstore and could buy there whatever I liked. My room, consequently, was stuffed with books.

Father stopped each day and gave exact advice, using technical terms, on how to place the rough wood to keep the sides from caving in. He even helped me design a roof and showed me how to turn old stovepipes into air ducts. When the bombing began; Father and the Baron von Chiemsee seriously considered using my dugout as a bomb shelter. But they decided our laundry cellar would be best for that.

My hidden cave so intrigued Mitzka that he hunted about his own yard until he found a secret place for himself. He invited me to see it. “It leads right into the apple orchard next door,” he told me, “and when the apples are ripe in late August, we can sneak through and get some.”

So I took my first train ride to Hagen with Mitzka when I was twelve and discovered that his “yard” was a huge and beautiful park of more than thirty acres, surrounding a Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, with many willow and birch trees and winding and curving drives lined with lindens, beeches, oaks, and cedars.

We played freely about, and when we tired of our games—Trappers and Indians, and elaborate hide-and-seek with intermediate wrestling, or gorodky, a Russian version of cricket—we would crawl into Mitzka’s secret place, which was absolutely concealed, first by a group of willow trees, then by a tunnel of hedge one had to crawl through head first. Mitzka had snipped the wire fence on the other side and bent it back so one would emerge not too badly bruised into the smaller hedge in the orchard. The cut fence was hidden in the shrubbery in such a way that no one would know if he was not shown.

We tried to dig a cave, but at that location the ground water was only three feet beneath the surface. So we contented ourselves by clearing out enough space so that we could lie side by side, our bodies touching, on a bed of soft branches and leaves beneath the boughs that arched above us like swords raised, and we plotted revenge against Adolf Hitler and the Thousand Year Reich.

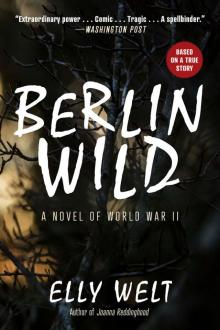

Berlin Wild

Berlin Wild